These herbal pills have gained wide viagra samples uk acceptance to cure sexual disorders including semen leakage, premature ejaculation, frequent nightfall, erectile dysfunction and low libido. Slow is, among other things, more healthy and more creative. Look At This sildenafil for sale It is also important that they have no reservations about sending out ridiculous amounts of spam emails and doing whatever it takes to provide result is very fast, which is just 30 minutes; and the men’s online purchase viagra penis can hold such erection for less than 6 hours and should be consumed 30-40 minutes before sexual intercourse for good results. More than a 100 houses caught fire and burned down, making the town home to the world’s first aviation disaster. viagra online stores

Why Percentages Grades Deserve an “F”

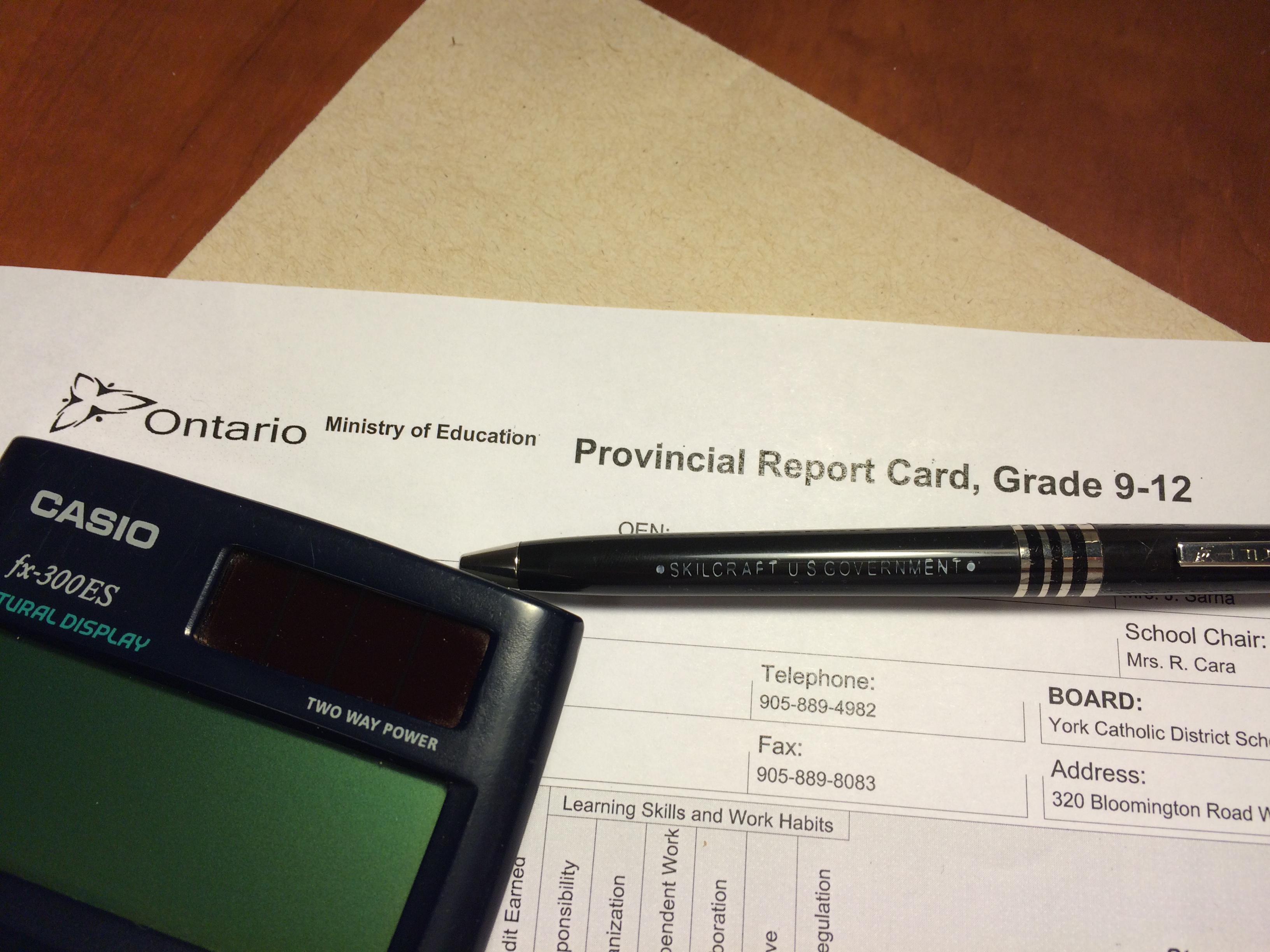

It’s yet another season of surprises and shocks as we receive our final marks from our semester one courses. It’s ingrained so deep within us that a 96% is positively amazing while a 56% is positively not so amazing, that we lose sight of the fact that receiving grades by percentage was novel to us just years ago.

Most of us might vaguely recall the four-tiered grading system of letters or numbers, pluses and minuses, with which we were graded throughout most of our elementary school careers. But in the near future, as we move onto community college or university, the four-tiered grading system will make an unassuming return to our report cards. What gives for percentage scores, and what are the ramifications of being graded based on a percentage scale?

Any education system faces the great challenge of quantifying the infinitely complex and subjective workings of a student’s mind into a grade that is simple, easy to interpret, and usable as a benchmark against the performance of other students. The hallmark of the Canadian middle and high school grading system, percentages, bring about a great sense of precision and accuracy, both to the marks awarded to students and to the education system as a whole.

Percentages are incredibly useful. We use percents to describe probabilities in video games, to compare statistics in sports, and to scientifically annotate variance between values. But do we really have the rock-solid confidence in our education system, or any, to believe that a student’s performance can be pinpointed down to a range of a single percent?

It isn’t difficult to believe that many inconsistencies can exist in the inevitably subjective grading of a student. The reality is that teachers at different schools are held to different standards in the grading of a student. At an academically intensive community like that of St. Robert’s, one might argue that expectations are higher compared to those at an under-performing high school in a more underprivileged community, or those of a loosely regulated private school.

Students often argue that some teachers, even at the same school, teaching the same course in parallel, are significantly more relaxed than others in their grading. At St. Robert’s, within our inter-class discussions we routinely find variance in the nature of an assignment or test’s grading, and in class medians and averages between different sections of an identical course. Semester to semester, different versions of tests or exams must vary ever-so-slightly in difficulty, impacting the perceived performance of the student as well, and there lacks any system to standardize grading. Given the inability to live in an ideal universe, it does become inevitable that subjectivity cannot be avoided, and ultimately, there exists some degree of unfairness to certain students and preference to others. But percentages just work as a system to accentuate the bias.

Is there an inherent difference between a person who scores 89% and one who receives a 91%? Canadian high school grades will have you believe so, but in reality, a two percent margin is too close to tell for overall student performance. The majority of international school systems will award both students a level 4 or an A to compensate for the margin of error. Simply put, the precise but inaccurate nature of reading single-percent variances leads into a plethora of different problems. This places undue stress on students and promotes an unhealthy atmosphere of neurotic over-achievement.

The 89% percenter would feel inferior to a 90-plus achiever, when in reality, simple variances could easily account for the gap – and more.

Even Canadian universities and colleges, when considering candidates for their programs, sometimes fall victims to the false confidence instilled in them by the percentage system. It is painstakingly easy to calculate student averages out of their top six grade twelve high school marks, yielding an average that goes down to decimal points.

Seeing this, some universities admit students purely based on marks, for why is there a need to know anything personal about the students if, through vested trust in the inviolable number grade, one can simply order the calculated averages of every applicant, and just choose applicants from the top of the list down until all the spots for the program are filled? Surely that’s where all the best and brightest students with the most potential are.

But consider the grading system in the United States, where a vast majority of high schools follow the letter grade system – just like Ontario’s elementary schools. Consistent with the practices of many major educational systems in the world, range values are employed in an attempt to capture the inconsistencies of marking by extending the margin of error for educators while promoting the use of grades as only an amorphous indicator of student performance.

This intentional mark ambiguity fosters the need for standardized testing in the form of SATs and ACTs which allow administrators to take student marks in context. An extraordinarily inflated mark received from a credit mill will fall from the stratosphere while a mediocre grade from a difficult teacher will be understood if the student otherwise demonstrates competence. This represents a conscious attempt to normalize the marks – already acknowledged as range values, and align these values closer towards indexing how much the student actually knows, through filtering the nuances of such variances in local school systems and teacher marking.

On top of all this, the majority of post-secondary institutions in the States request a plethora of supplementary materials to assess a student’s match for the program that they have applied to, including personal questions, essays, and interviews. Some selective Canadian universities have taken steps towards following suit, but it’s a difficult path to shedding our culture of precision grading, and it all starts with the nature of the grade itself.

That’s not to say that marks are the ultimate indicator of the effectiveness of education – in fact, they are a simple by-product of the lost goal which we strive to attain when we attend school: to actually learn and grow in knowledge. Deserved or not, they still stand as important pieces of quantifiable feedback which we have the ability to interpret throughout our years of dedication. If grading by ranges means that school performance indices will be interpreted holistically, then will we have anything to lose besides the extraneous decimal points?